Crucifixes in the Museumsdorf Bayerischer Wald

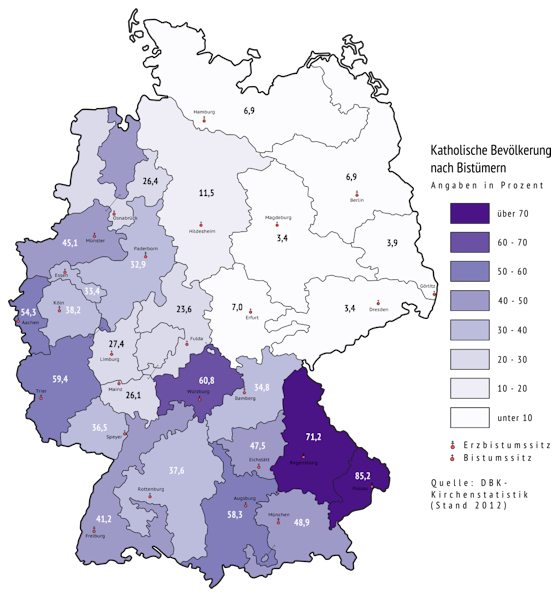

Bavaria has been overwhelmingly Roman Catholic for centuries. Even today, Bavaria contains the highest percentage of Catholics of any state in Germany, as the following map from the German Bishops’ Conference (Deutsche Bischofskonferenz) shows. This faith helped define the identities of the Bavarians of former days, and it wove itself deeply into the fabric of their lives. Signs of it were everywhere at the Museumsdorf Bayerischer Wald, the living history museum in Tittling, Germany, from outdoor shrines and miniature wayside chapels to crucifixes and pictures in every furnished house.

Percentage of Catholics by diocese in Germany, 2012 (katholische Bevölkerung nach Bistümern)

The chapel pictured below could hold only eight or ten people. It has the words, “Heiliger Florian beschütze uns for Feuer,” or “Saint Florian, protect us from fire,” written over the door. St. Florian, a Roman soldier in the late 200s AD, organized and trained an elite firefighting brigade. During one of the many religious persecutions of the time, he was sentenced to be burnt at the stake, but he seemed so eager to die this way that his executioners lost their nerve and drowned him instead. Because of his connection to firefighting, St. Florian has been invoked all over Europe for over a thousand years as a protector against the deadly fires that used to sweep through cities and villages.

Wayside chapel to St. Florian at the Museumsdorf Bayerischer Wald

In addition to buildings and shrines, the museum contained an indoor exhibition of small religious objects, such as the crucifixes pictured above. In the days before plastics and mass production, each of these items was handmade, so even though they were similar, they showed interesting variations, like the Pietà sculptures pictured below of Christ’s Mother holding her dead Son. In the sculpture on the right, her heart is pierced with swords, representing the seven great sorrows of her life. One of the swords is missing.

Pieta sculptures in the Museumsdorf Bayerischer Wald

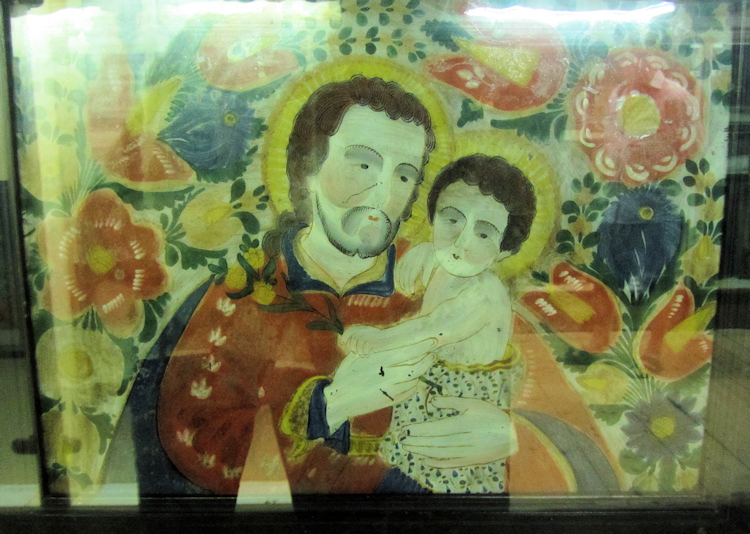

Folk art has a common style around the world, incorporating bright colors and flattened features. This primitive painting of St. Joseph with the Christ Child reminded me of paintings from Mexico.

After the invention of printing, colorful illustrations became cheaper and cheaper, and people across Europe looked for ways to decorate their homes with these pretty pictures. In England, the Victorians experimented with cut paper art, and around the same time, someone in Bavaria must have been doing the same thing. The altar below is a masterpiece of cut and glued paper, foil, and other inexpensive materials. It’s only about eleven inches high.

Miniature altar in the Museumsdorf Bayerischer Wald

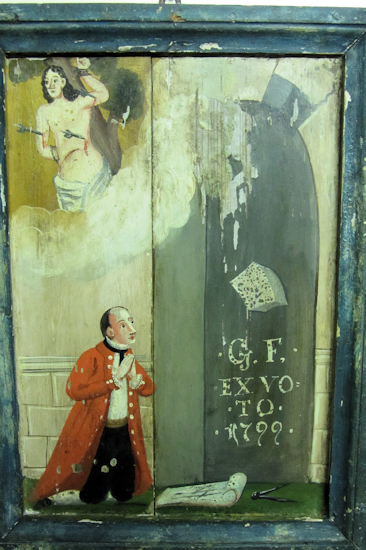

One of the things that fascinated me the most was the museum’s collection of votive plaques. People had commissioned these to express their thanks for an answered prayer, and that means each plaque had a story to tell.

Votive plaque at the Museumsdorf Bayerischer Wald

This votive plaque from 1799 especially caught my interest. The man in the foreground is wearing the clothes of a gentleman, and he’s carrying blueprints and drafting tools. We can see an arch crumbling beside him. If the damage were nothing more than the single block falling down, he wouldn’t have had time to pray for help, but as it is, this plaque tells us that he called on St. Sebastian, pictured in the upper left. Perhaps he was the architect of a building that caved in. This plaque tells us that St. Sebastian answered his prayer and saved his life.

To read my latest blog posts, please click on the “Green and Pleasant Land” logo at the top of this page. All photos taken in June, 2014, at the Museumsdorf Bayerischer Wald, Tittling, Germany. Photos and text copyright 2014 by Clare B. Dunkle.

It would be especially ironic if he’d been the architect and his building had fallen down UPON him – I do wonder if St. Sebastian still saves you if your trouble is your own fault. ☺

As always, these are so ornate and symbolic – myriad swords to the heart and all. They make me smile, but gently – in acknowledgement of true sincerity. That’s why I love religious art, too.