The other day, a television vet was called out to examine a young Waschbär. What kind of “bear” is this? It’s the kind known for waschen–washing its food. Der Waschbär is a raccoon. Wild raccoons don’t ordinarily wash their food, so the reason behind the washing is a mystery. But der Waschbär has very sensitive front paws and likes to manipulate objects with them, and it also does a lot of fishing and hunting in the water of riverbanks for its prey. So when a captive raccoon takes its food to its bowl to “wash” it, it’s probably acting out normal hunting techniques. Interestingly enough, our word “raccoon” comes from a Powhatan term for “the one who scratches or scrubs”–in other words, der Waschbär.

The Grandfather of Comics

My friend Heidi recently loaned me her childhood copy of the Wilhelm Busch stories. Wilhelm Busch created Max & Moritz, the devilish duo who came on the scene in 1865 and inspired the modern comic book. Combine the morbid satire of Edward Gorey with the jaunty rhymes and rowdy anarchy of Dr. Seuss, and you have a can’t-miss recipe for fun.

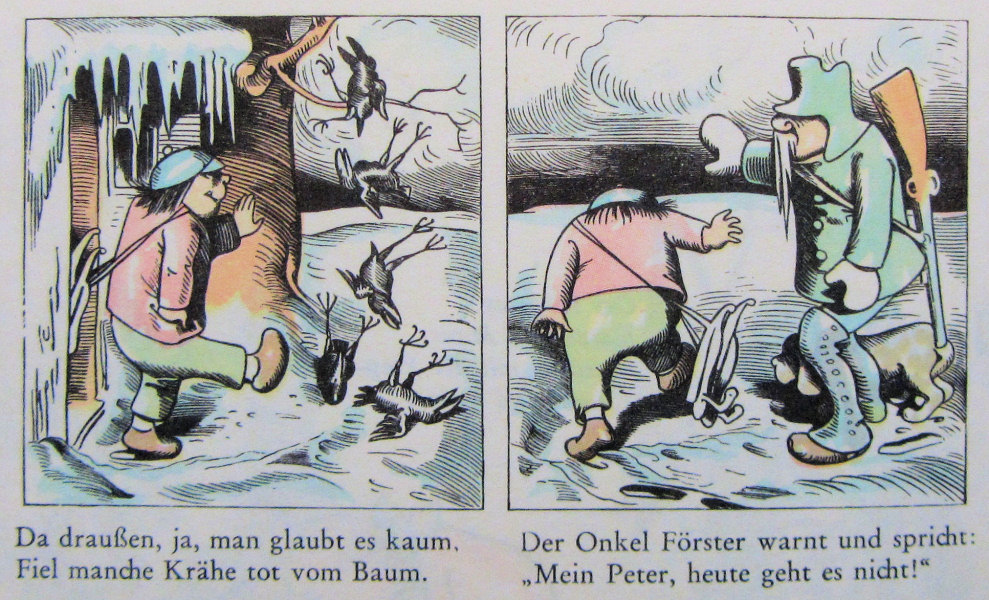

Eispeter came out the year before Max & Moritz. It has a moral, yes, but that’s not the point: in Busch’s day, the stern moral was already obligatory, but Busch provided the fun. Here we see Peter determined to go out skating even though the day is too cold. Crows are falling dead from the trees, and his uncle warns him, but Peter’s smug grin says it all. The portrait of moronic youth hasn’t changed much in a hundred and fifty years, has it?

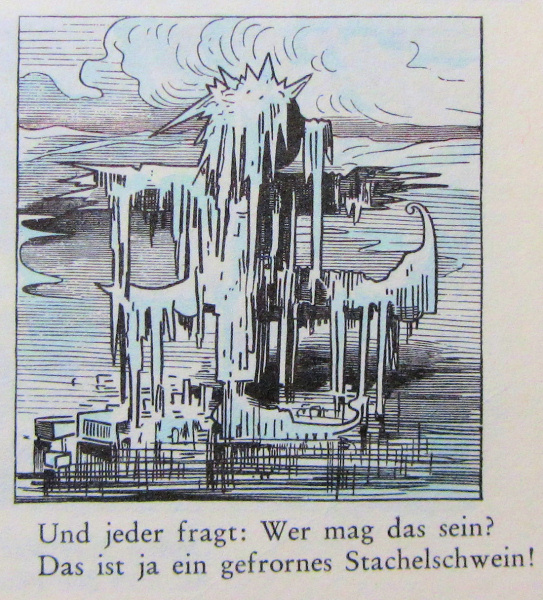

Peter loses half his britches when they freeze to a stone. Naturally, he then falls into a hole in the ice. This is the result:

Peter has become a frozen Stachelschwein, a porcupine of icicles. The tail you see is his underwear, hanging out of the hole in his pants and frozen solid.

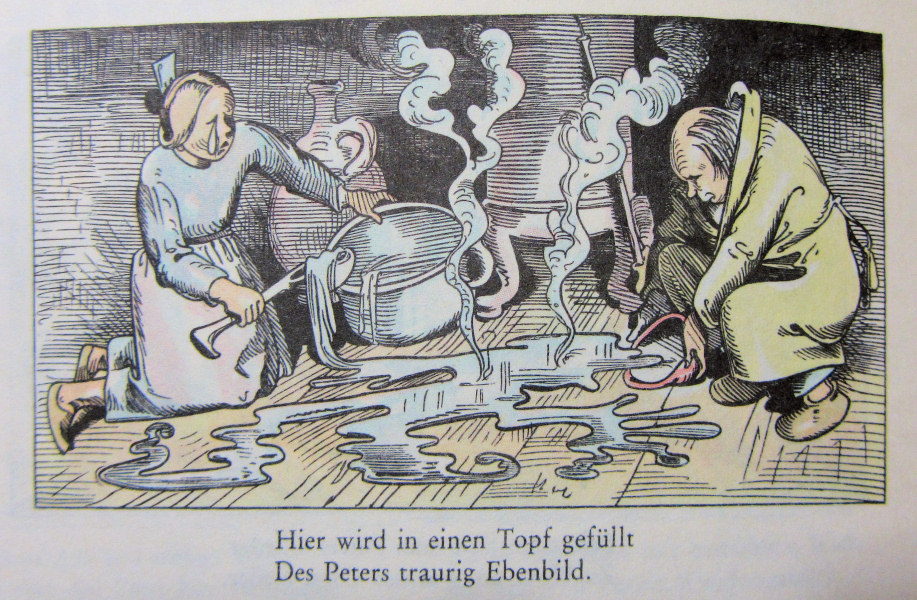

Of course, the family goes in search of their lost Schlingel (bad boy). They bring home the porcupine sculpture and are happy when the ice begins to melt. But Peter melts into a kind of runny slop (still roughly boy-shaped). His parents are inconsolable:

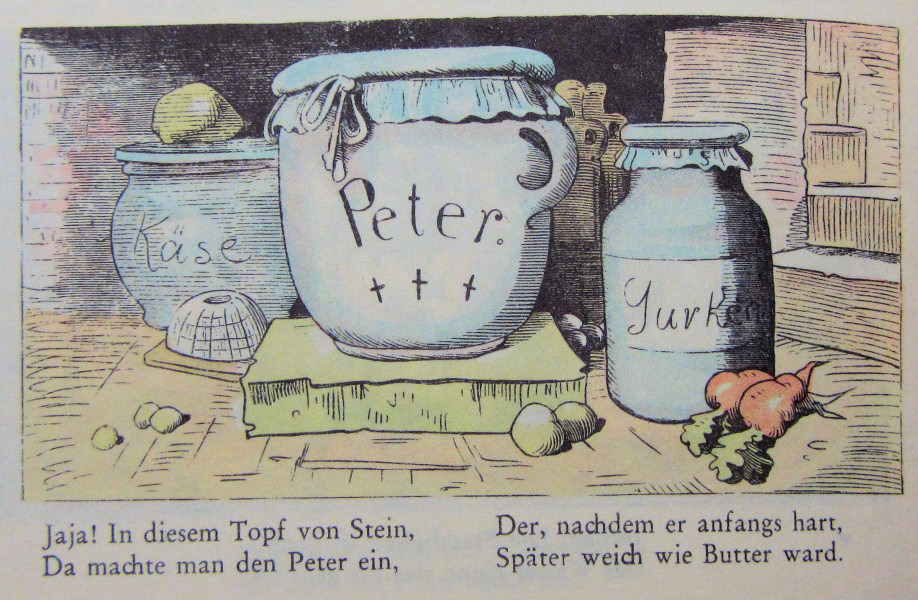

What becomes of our naughty boy? Peter is “preserved” in a jam pot! His mortal remains sit in the pantry next to the pickles and cheese:

No wonder these hysterical little stories launched an entire genre!

Photos taken in October, 2011, in Rodenbach, Germany. Text copyright Clare B. Dunkle. Photos are not subject to copyright as they are faithful reproductions of old, public domain, two-dimensional works of art.

Last night, I was watching one of the many World War II documentaries that appear on German television. This one concerned the battles in north Africa. An old British soldier stated in voice-over German that although things looked bad, General Montgomery would not even allow his men to utter the word Niederlage. What were they forbidden to mention? Nieder means down or low, and die Lage means situation, position, or attitude. The forbidden word die Niederlage, therefore, means defeat.

A Fish out of Water

When I was a little girl in Denton, Texas, my brothers and I played with the Goetz boys, who lived around the corner. We were terribly excited when they arrived because they came from Germany. (Our experience of Germans up to that point had been World War II movies.) The boys soon became regular Americans, and Mrs. Goetz awed me a little because she was always so busy. It was Mr. Goetz who ultimately captured my imagination. In spite of the years that passed, he continued to seem exotic, romantic … and wistful.

Mr. Goetz was a Bavarian. I remember him as compact and stoop-shouldered, like the man in the photo. His German was soft, not at all like the harsh, gutteral German of our favorite war movies, and the adjective “gentle” could have been invented just to describe him. He was a woodcarver of beautiful, deeply Catholic pieces. He must have grown up enjoying the exuberant Bavarian style that falls somewhere between baroque art and rustic decoration.

But Denton, Texas had no beauty of this kind. Our church was modern. In fact, I remember no real beauty of any kind in the 1960’s ranch houses, wide asphalt streets, and sticker-covered landscapes of my childhood. Certainly it didn’t look like this:

As I got older, Mr. Goetz would take out books and maps to show me the Bavaria he had left behind. He told me about walking in the mountains and smelling the chocolate flower. This Texas child couldn’t make her limited experience of the rough young Rockies match up with his descriptions of the beautiful Alps. He might as well have been describing the moon.

I didn’t expect ever to see Germany, much less to live here. But when I did come to Bavaria, I had the vague idea that it wouldn’t look as colorful as Mr. Goetz’s books and memories. I was wrong. And as strong as the ties of Bavarian culture are, I can see why Mr. Goetz couldn’t let it go. If I were a Bavarian transplanted to the parched pastureland of north Texas, I think it would break my heart.

Photos taken in October, 2011, in Garmish-Partenkirchen, Germany. Text and photos copyright 2011 by Clare B. Dunkle and Joseph R. Dunkle.

In honor of our recent trip to Bavaria, I’m featuring a very useful word that has no real English equivalent: der Stau. Anyone who lives in Germany longer than a few weeks comes to know and use this word. German autobahns have no access roads like American highways do, so when traffic gets heavy or when two (or eight) cars smash into one another, there’s not much the drivers behind can do but wait for the mess to sort itself out. This results in a Stau–a temporary parking lot on the autobahn. You might call it a traffic jam, but the word Stau is more precise and also easier to say. German radios reporting on traffic routinely attach lengths to their Stau warnings: sechs Kilometer Stau, for example. This article tells us about a 60 Kilometer Stau in Austria.

Art from life

I took this photo from my hotel balcony last weekend on the evening of our arrival in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. We stayed at Hotel Schatten on the Partenkirchen side, and I heartily recommend it. The church you see is Pfarrkirche Maria Himmelfahrt, the Church of the Assumption. The famous Wetterstein Alps are nonexistent.

As I snap the picture, am I disappointed? Not a bit!

It’s a truism that we write what we know. My books come out of my own imagination, of course, but unless I’ve gone to the trouble to feed that imagination with facts, concepts, and experiences, my writing won’t have enough depth to help readers suspend their disbelief. The rocky foundation of a great fantasy world, therefore, is a wide-ranging exposure to the world we all live in. Everything matters, from the tiniest moss to the biggest mountain.

So, when I learned that our trip to Bavaria would be dogged by bad weather, I was thrilled. Anybody can open a coffee table book and look at photos of mountains under blue sky. But how many authors can accurately describe the mountains in rain … mist … snow?

This is the same view by late morning the next day. The bright mist rising out of the trees changes constantly. The nearby Kochelberg and Hausberg hills have put in an appearance. Their light dusting of snow is already beginning to melt.

Late afternoon, and here are the mountains at last. It turns out that we have a stunning view of the Alpspitze, 8622 feet high (2628 m), already starting to don its winter coat of snow. But yesterday, it belonged to the clouds. Not for nothing is this part of the Alps called the Wetterstein–the “weather stone” range.

Photos taken in October, 2011, from the balcony of the Hotel and Gasthof Schatten, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany. Text and photos copyright 2011 by Clare B. Dunkle.

The other day, I was walking down a fairly steep hill when two little girls swept by me on tiny bicycles, wobbling along and picking up speed. Behind them trotted their anxious mother, shouting, “Bremse! Bremse!” Die Bremse, of course, is the brake.

An Afternoon Walk around Rodenbach

The town I live in is like Grandma’s cookie jar: I never know what I’ll find when I shut my front door and walk outside, but I can be pretty sure I’m going to love it. There are lots of enjoyable things to see within ten minutes of my house.

On the hill above my street is a Reitstall: a riding stable. I snapped this action shot of a horse heading back to his stall, and considering my general ineptitude with a camera, I was very pleased with how it turned out. My camera, fortunately, is much smarter about taking pictures than I am. It’s a Canon PowerShot SX230 HS.

The number of horses around here amazes me. In my opinion, it’s a good measure of the prosperity of the local residents. Horses are like yachts: a true luxury item.

This lovely monument is just outside the Reitstall. It used to be a tradition in this part of Germany to have a cross wherever two roads meet, and there are many other sculptures and shrines as well.

I’ve read about dairy cows lying down in the fields, but I never noticed it in Texas. Here in Germany, though, the entire herd will be lying around and dozing in the afternoon. They look very peaceful.

And this lovely little fountain is in a front garden just down the street from my apartment.

Photos taken in October, 2011, in or near Rodenbach, Germany. Text and photos copyright 2011 by Clare B. Dunkle.

In honor of the end of Oktoberfest in Munich, Bavaria, today’s word is die Maßkrugschlägerei. It’s a compound word, and sometimes hyphenated. You’re not likely to find it in your dictionary. Nevertheless, it’s a very handy word to know. Der Maßkrug is a glass or ceramic beer mug that holds a liter of alcohol. (This is the standard-size mug at Oktoberfest!) Die Schlägerei is a brawl or a fight involving physical assaults. Put them together, and you have die Maßkrugschlägerei: a brawl in which a heavy beer mug is used as a weapon. According to this fun article from Spiegel Online International, there were 58 incidents of Maßkrugschlägerei at this year’s Oktoberfest. Since 7.5 million liters of beer were served–each in its official Maßkrug–that’s a pretty low number!

As American as…

The other day, I caught a few minutes of a Bavarian cooking show. Six Landfrauen were sitting down to a dinner prepared by a seventh Landfrau. Beautiful table. Elaborate menu. Strong, confident women who looked good in dirndls and who could say things like “That’s not MY recipe for Rinderlende mit Rotweinsoße und Reibernockerl dazu Blaukrautscheiben, but oh, well.”

A Landfrau. A woman of the land. Everything I’m NOT–but wish I could be.

So I got inspired to make an apple blueberry pie. But we couldn’t find fresh blueberries. We couldn’t find measuring cups, either. Time to improvise. A Pilsner beer glass had its markings in milliliters. We used one of our teacups, figured out the conversion, and presto! I had a 3/4 cup measuring cup … more or less. I had no recipe books, either, so I opened up the computer and did a search for my pie crust recipe. The first thing I read was “You are not eligible to join the Betty Crocker community.” Ouch! They know me too well.

But making the crust restored my confidence. I’ve been making pies since I was old enough to stand on a step stool beside my Texan grandmother. (Now, she’s a Landfrau!) Germans believe a beer should contain only four ingredients: malt, hops, yeast, and water. I believe a pie crust should contain only four ingredients: flour, butter (real butter!), water, and salt. (Shortening is an abomination.) No pastry cutter. I used herb scissors instead. Then I had no rolling pin. Never mind–a wine bottle works just as well. It could be full or empty. This one is empty. What can I say? I live in Europe!

I used my usual apple blueberry pie recipe, except that I used frozen blueberries. Also a crust instead of the topping and a pinch of ginger to bring out the cinnamon. And I used more cinnamon. (A real Landfrau never follows a recipe exactly.)

What can I say? It tasted like home. Maybe I’m a Landfrau after all.

Photos taken in October, 2011, in Rodenbach, Germany. Text and photos copyright 2011 by Clare B. Dunkle.